TANT 10 - Inverse limits and examples of local fields

Hello there! These are notes for the ninth class of the course "Topics in algebra and number theory" held in Block 4 of the academic year 2017/18 at the University of Copenhagen.

In the previous lecture we have given a complete characterization of non-Archimedean fields which are locally compact. In particular, we have seen that they are all finite extensions of \( \mathbb{Q}_p \) or \( \mathbb{F}_p((T)) \). Today we are going to study more these two fields, giving an alternative description of them which uses inverse limits.

Definition 1 A (upward) directed set is a set \( I \) with an order relation \( \leq \) such that for every \( i, j \in I \) there exists \( k \in I \) with \( k \geq i \) and \( k \geq j \).

Definition 2 An inverse system of groups (or rings, sets, topological spaces ... and in general in any category \( \mathcal{C} \) ) consists of a collection \( \{ X_i \}_{i \in I} \) of groups (or rings, etc...) indexed on a directed set \( I \) and a collection of maps \( \{ f_{i,j} \colon X_j \to X_i \} \) for every \( i \leq j \) such that \( f_{i, i} \) is the identity map for all \( i \in I \) and \( f_{i, k} = f_{i, j} \circ f_{j, k} \) for all \( i \leq j \leq k \).

It would be nice if we could encompass all the properties of this system in one single object which takes into account all the objects \( X_i \) and all the maps \( f_{i,j} \). So nice that this object deserves a name.

Definition 3 Let \( ( \{ X_i \}, \{ f_{i,j} \} ) \) be an inverse system of groups (or rings, etc...). A cone for this inverse system is a group (or a ring, etc...) \( C \) with maps \( f_i \colon C \to X_i \) such that \( f_i = f_{i,j} \circ f_j \) for all \( i \leq j \). An inverse limit for this system is a cone \( X \) with maps \( \pi_i \colon X \to X_i \) such that for every other cone \( C \) with maps \( f_i \colon C \to X_i \) there exists a unique map \( f \colon C \to X \) such that \( f_i = \pi_i \circ f \).

Exercise 4 Let \( X \) and \( X' \) be two inverse limits for the same inverse system \( ( \{ X_i \}, \{ f_{i,j} \} ) \). Prove that they are isomorphic. Thus we can speak of the inverse limit of a given inverse system (provided that it exists!) and we denote it by \( \varprojlim_i X_i \).

The key property of the categories of rings, sets, topological spaces (and many more...) is that we can always construct an inverse limit for a given inverse system! Indeed let \( ( \{ X_i \}, \{ f_{i,j} \} ) \) be an inverse system and consider the subset \( X \) of the product \( \prod_i X_i \) given by all the sequences \( \mathbf{x} = (x_i)_i \in \prod_i X_i \) such that \( f_{i,j}(x_j) = x_i \) for all \( i \leq j \). If the \( X_i \)'s are groups (resp. rings, topological spaces...) then this is a subgroup (resp. a subring, a subspace...) of the product \( \prod_i X_i \), and we have the projection maps \( \pi_i \colon X \to X_i \) given by restricting the usual projection maps \( \prod_i X_i \twoheadrightarrow X_i \). It is immediate to see that \( X \) with these projection maps is a cone for the inverse system \( ( \{ X_i \}, \{ f_{i,j} \} ) \). Moreover for every other cone \( C \) with maps \( f_i \colon C \to X_i \) we know already that there exists a map \( \widehat{f} \colon C \to \prod_i X_i \) simply given as the product of all the maps \( f_i \). Let now \( c \in C \) and observe that \( f_{i,j}(f_j(c)) = f_i(c) \), which implies that \( \widehat{c} = (f_i(c))_i \in X \). Thus we get a map \( f \colon C \to X \) such that \( f_i = \pi_i \circ f \) for every \( i \in I \). This implies indeed that \( X \) is an inverse limit for the inverse system \( ( \{ X_i \}, \{ f_{i,j} \} ) \).

Example 5 Let \( K \subseteq L \) be a Galois extension of fields. Then the set of all subextensions \( K \subseteq M \subseteq L \) such that \( K \subseteq M \) is a finite extension is directed with respect to inclusion. Moreover for every \( (K \subseteq) M \subseteq N (\subseteq L) \) we have a map \( \operatorname{Gal}(N/K) \to \operatorname{Gal}(M/K) \), and these all together form an inverse system. It is not difficult to prove that \( \operatorname{Gal}(L/K) \) is an inverse limit for this system, with projection maps \( \operatorname{Gal}(L/K) \to \operatorname{Gal}(M/K) \) given by restriction.

Remember that in the first lecture we defined the ring \( \mathbb{Z}_p \) as the inverse limit \( \varprojlim_r \mathbb{Z}/p^r \mathbb{Z} \) without defining what an inverse limit is! Now that we know this, we can go back and try to understand what a p-adic number really is, as we will do in the next section.

Moreover, we can use inverse limits to give another description of the ring \( A_{\phi} \) associated to a non-Archimedean absolute value \( \phi \colon K \to \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} \). In order to do so, we need to define a new way to put a topology on any ring.

Definition 6 Let \( R \) be a ring, and \( I \subseteq R \) be an ideal. The \( I \)-adic topology on \( R \) is the coarsest topology such that \( x + I^n \) is open for all \( x \in R \) and \( n \in \mathbb{N} \).

Exercise 7 Let \( R \) be a ring, and \( I \subseteq R \) be an ideal. Show that the maps

\[ \begin{aligned}

R \times R &\to R \\

(x,y) &\mapsto x + y

\end{aligned} \qquad \text{and} \qquad \begin{aligned}

R \times R &\to R \\

(x,y) &\mapsto x y

\end{aligned}

\] are continuous with respect to the \( I \)-adic topology, i.e. \( R \) is a topological ring with respect to the \( I \)-adic topology.

We have already encountered many examples of \( I \)-adic topologies, as it is shown in the following exercise.

Exercise 8 Let \( (K,\phi) \) be a non-Archimedean, discretely valued field. Prove that the subspace topology induced on \( A_{\phi} \) coincides with the \( \mathfrak{m}_{\phi} \)-adic topology.

The properties of completeness and separateness of the \( I \)-adic topology, which we recall in the following definition, can be detected by means of an inverse limit, as we see in the next proposition.

Definition 9 Let \( X \) be a topological space. We say that:

Observe that every topological ring \( R \) is also a topological abelian group. Thus when we say that \( R \) is complete (or that a sequence is Cauchy in \( R \) ) we consider \( R \) as a topological abelian group.

Proposition 11 Let \( R \) be a ring, and let \( I \subseteq R \) be an ideal. Then \( R \) is separated with respect to the \( I \)-adic topology if and only if the map \begin{align} \varphi \colon R &\to \varprojlim_n R/I^n \\ x &\mapsto (x \, \text{mod} \, I^n)_n \end{align} is injective, and it is complete if and only if \( \varphi \) is surjective.

Proof Observe that \( \varphi \) is injective if and only if for every \( x, y \in R \) with \( x \neq y \) there exists \( n \in \mathbb{N} \) such that \( x \not\equiv y \, \text{mod} \, I^n \). This is equivalent to say that for every \( x, y \in R \) with \( x \neq y \) there exists \( n \in \mathbb{N} \) such that \( x + I^n \cap y + I^n = \emptyset \), i.e. that \( R \) is separated with respect to the \( I \)-adic topology.

Observe now that a sequence \( \{ x_n \} \subseteq R \) is Cauchy if and only if for every \( N \in \mathbb{N} \) there exists \( n_0 \in \mathbb{N} \) such that for all \( n, m \in \mathbb{N}_{\geq n_0} \) we have that \( x_n - x_m \in I^N \).

Suppose now that \( R \) is complete with respect to the \( I \)-adic topology. Let now \( \mathbf{x} = (x_n \, \text{mod} \, I^n) \in \varprojlim_n R/I^n \) and observe that the sequence \( \{ x_n \} \subseteq R \) is Cauchy, because by definition of the inverse limit we have that \( x_n - x_m \in I^m \) for all \( n \geq m \). Thus let \( x_{\infty} \in R \) be the limit of \( \{ x_n \} \) and observe that \( x_{\infty} - x_n \in I^n \) for all \( n \in \mathbb{N} \), i.e. that \( \varphi(x_{\infty}) = \mathbf{x} \) and thus \( \varphi \) is surjective.

Vice versa if \( \varphi \) is surjective and \( \{ x_n \} \subseteq R \) is a Cauchy sequence we can always find a subsequence \( \{ y_k = x_{n_k} \) such that \( y_k - y_l \in I^l \) for all \( k \geq l \). If we do so then \( \mathbf{y} := (y_k \, \text{mod} \, I^k) \in \varprojlim_k R/I^k \) and since \( \varphi \) is surjective we can find \( y_{\infty} \in R \) such that \( \varphi(y_{\infty}) = \mathbf{y} \). It is really easy to see now that \( \{ y_k \} \) converges to \( y_{\infty} \), which implies that \( \{ x_n \} \) also converges to \( y_{\infty} \) because the sequence \( \{ x_n \} \) is Cauchy. Q.E.D.

Corollary 12 Let \( (K,\phi) \) be a non-Archimedean, discrete valued field, and let \( \pi \in K \) be a uniformizer. Then \( (K,\phi) \) is complete if and only if the map

\begin{align} \left( \dagger \right) \colon A_{\phi} &\to \varprojlim_n A_{\phi}/\pi^n A_{\phi} \\ x &\mapsto (x \, \text{mod} \, \pi^n)_n \end{align} is an isomorphism.

Proof Using the previous proposition we see that \( \left( \dagger \right) \) is an isomorphism if and only if \( A_{\phi} \) is complete with respect to the \( \mathfrak{m}_{\phi} \)-adic topology. To conclude we simply need to observe that this topology coincides with the subspace topology induced by \( K \) (thanks to Exercise 8) and that \( K \) is complete if and only if \( A_{\phi} \) is complete because we can write \( K = \bigcup_{i \in I} x_i + A_{\phi} \) for some \( \{ x_i \} \subseteq K \) representing the quotient of abelian groups \( K/A_{\phi} \). Q.E.D.

Corollary 13 Let \( (K, \phi) \) be a non-Archimedean, discretely valued field, and let \( (K_{\phi}, \Phi) \) be its completion. Then we have that \[ A_{\Phi} \cong \varprojlim_n A_{\phi}/\pi^n A_{\phi} \] where \( \pi \in K \) is any uniformizer.

Suppose now that \( K \) is non-Archimedean. Then \( \phi(K^{\times}) \) is discrete and we can describe the ring \( A_{\phi} \) as \[ A_{\phi} = \left\{ \sum_{k = 0}^{+\infty} a_k \pi^k \mid a_k \in S \right\} \] where \( S \subseteq K \) is any set of representatives for the quotient \( A_{\phi}/\mathfrak{m}_{\phi} \) which contains zero (this is Corollary 8 of the previous lecture) or as \[ A_{\phi} \cong \varprojlim_n A_{\phi}/\pi^n A_{\phi} \] using Corollary 12. In particular if \( K \) is the completion of a field \( F \subseteq L \) then we can use Corollary 13 to write \[ A_{\phi} \cong \varprojlim_n R/t^n R \], where \( R := A_{\phi} \cap F \) and \( t \in F \) is a uniformizer.

Example 14 Let \( F \) be any field, and consider the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \colon F(T) \to \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} \) defined by \( \lvert f(T) \rvert_T := c^{-\operatorname{ord}_T(f(T))} \), where \( \operatorname{ord}_T(f(T)) := \max\{ n \in \mathbb{N} \colon T^n \mid f(T) \} \) and \( c \in \mathbb{R}_{> 1} \) is any constant. Observe that \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \) is non-Archimedean and that \( \lvert T \rvert_T = c^{-1} < 1 \). Thus for every sequence \( \{ a_n \} \subseteq F \) we have that the sequence of partial sums \( \left\{ \sum_{j = 0}^n a_j T^j \right\}_n \subseteq F(T) \) is a Cauchy sequence with respect to \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \).

Consider now the field of formal Laurent series \( F((T)) \) that we defined in Example 12 of the previous lecture. Then we have an embedding \( F(T) \hookrightarrow F((T)) \) given by extending the obvious inclusion of integral domains \( F[T] \hookrightarrow F[[ T ]] \) to their fields of fractions. Moreover the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \) extends to \( F(( T )) \) by setting \[ \left\lvert \sum_{n = n_0}^{+\infty} a_n T^n \right\rvert := c^{-n_0} \qquad \text{where} \qquad a_{n_0} \neq 0 \] and it is not difficult to see that \( F(( T )) \) is complete with respect to this absolute value. Indeed a sequence \( \left\{ \sum_{k = k_0^n} a_k^n T^k \right\}_n \subseteq F(( T )) \) is Cauchy if and only if the sequence \( \{ k_0^n \}_n \) has a minimum \( k_0^{\infty} \) and for every \( k \in \mathbb{Z}_{\geq k_0^{\infty}} \) there exists \( n_k \in \mathbb{N} \) such that for every \( l \in \mathbb{N}_{\leq k_0} \) and for every \( n, m \in \mathbb{N}_{\geq n_k} \) we have that \( a_l^n = a_l^m \). Thus we can define a new sequence \( a_k^{\infty} := a_k^{n_k} \) and it is easy to see that \( \sum_{k = k_{0}^{\infty}}^{+\infty} a_k^{\infty} T^k \) is the limit of the Cauchy sequence that we started from.

Finally if \( F(T) \to L \) is a morphism of valued fields we can use the fact that any sequence of partial sums \( \left\{ \sum_{j = 0}^n a_j T^j \right\}_n \) is Cauchy (if \( \{ a_j \}_j \subseteq F \)) to see immediately that this morphism extends (uniquely) to a map \( F(( T )) \to L \). Thus we have proved that \( F(( T )) \) is the completion of \( F(T) \) with respect to the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \).

To do so in an effortless way we could observe that \( T \in F(T) \) is a uniformizer for the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \) and thus if \( (K,\Phi) \) is any completion of \( (F(T), \lvert \cdot \rvert_T) \) we have that \[ A_{\Phi} = \left\{ \sum_{k = 0}^{+\infty} a_k T^k \mid a_k \in F \right\} \cong F[[ T ]] \] which implies that \( K \cong F(( T )) \).

We can do something similar for the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_p \) on the field \( \mathbb{Q} \).

Definition 15 The field of p-adic numbers \( \mathbb{Q}_p \) is the completion of the field \( \mathbb{Q} \) with respect to the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_p \). We denote its unit ball by \( \mathbb{Z}_p \) and we call it the ring of p-adic integers.

We can give two alternative descriptions of \( \mathbb{Q}_p \) as follows:

In the previous lecture we have given a complete characterization of non-Archimedean fields which are locally compact. In particular, we have seen that they are all finite extensions of \( \mathbb{Q}_p \) or \( \mathbb{F}_p((T)) \). Today we are going to study more these two fields, giving an alternative description of them which uses inverse limits.

Inverse limits

We recall here the definitions of inverse system and inverse limit, which will be crucial in the following weeks of the course.Definition 1 A (upward) directed set is a set \( I \) with an order relation \( \leq \) such that for every \( i, j \in I \) there exists \( k \in I \) with \( k \geq i \) and \( k \geq j \).

Definition 2 An inverse system of groups (or rings, sets, topological spaces ... and in general in any category \( \mathcal{C} \) ) consists of a collection \( \{ X_i \}_{i \in I} \) of groups (or rings, etc...) indexed on a directed set \( I \) and a collection of maps \( \{ f_{i,j} \colon X_j \to X_i \} \) for every \( i \leq j \) such that \( f_{i, i} \) is the identity map for all \( i \in I \) and \( f_{i, k} = f_{i, j} \circ f_{j, k} \) for all \( i \leq j \leq k \).

It would be nice if we could encompass all the properties of this system in one single object which takes into account all the objects \( X_i \) and all the maps \( f_{i,j} \). So nice that this object deserves a name.

Definition 3 Let \( ( \{ X_i \}, \{ f_{i,j} \} ) \) be an inverse system of groups (or rings, etc...). A cone for this inverse system is a group (or a ring, etc...) \( C \) with maps \( f_i \colon C \to X_i \) such that \( f_i = f_{i,j} \circ f_j \) for all \( i \leq j \). An inverse limit for this system is a cone \( X \) with maps \( \pi_i \colon X \to X_i \) such that for every other cone \( C \) with maps \( f_i \colon C \to X_i \) there exists a unique map \( f \colon C \to X \) such that \( f_i = \pi_i \circ f \).

Exercise 4 Let \( X \) and \( X' \) be two inverse limits for the same inverse system \( ( \{ X_i \}, \{ f_{i,j} \} ) \). Prove that they are isomorphic. Thus we can speak of the inverse limit of a given inverse system (provided that it exists!) and we denote it by \( \varprojlim_i X_i \).

The key property of the categories of rings, sets, topological spaces (and many more...) is that we can always construct an inverse limit for a given inverse system! Indeed let \( ( \{ X_i \}, \{ f_{i,j} \} ) \) be an inverse system and consider the subset \( X \) of the product \( \prod_i X_i \) given by all the sequences \( \mathbf{x} = (x_i)_i \in \prod_i X_i \) such that \( f_{i,j}(x_j) = x_i \) for all \( i \leq j \). If the \( X_i \)'s are groups (resp. rings, topological spaces...) then this is a subgroup (resp. a subring, a subspace...) of the product \( \prod_i X_i \), and we have the projection maps \( \pi_i \colon X \to X_i \) given by restricting the usual projection maps \( \prod_i X_i \twoheadrightarrow X_i \). It is immediate to see that \( X \) with these projection maps is a cone for the inverse system \( ( \{ X_i \}, \{ f_{i,j} \} ) \). Moreover for every other cone \( C \) with maps \( f_i \colon C \to X_i \) we know already that there exists a map \( \widehat{f} \colon C \to \prod_i X_i \) simply given as the product of all the maps \( f_i \). Let now \( c \in C \) and observe that \( f_{i,j}(f_j(c)) = f_i(c) \), which implies that \( \widehat{c} = (f_i(c))_i \in X \). Thus we get a map \( f \colon C \to X \) such that \( f_i = \pi_i \circ f \) for every \( i \in I \). This implies indeed that \( X \) is an inverse limit for the inverse system \( ( \{ X_i \}, \{ f_{i,j} \} ) \).

Example 5 Let \( K \subseteq L \) be a Galois extension of fields. Then the set of all subextensions \( K \subseteq M \subseteq L \) such that \( K \subseteq M \) is a finite extension is directed with respect to inclusion. Moreover for every \( (K \subseteq) M \subseteq N (\subseteq L) \) we have a map \( \operatorname{Gal}(N/K) \to \operatorname{Gal}(M/K) \), and these all together form an inverse system. It is not difficult to prove that \( \operatorname{Gal}(L/K) \) is an inverse limit for this system, with projection maps \( \operatorname{Gal}(L/K) \to \operatorname{Gal}(M/K) \) given by restriction.

Inverse limits and completeness

So, this notion of inverse limit seems very powerful and versatile, but... it is useful in this course? Indeed it is, and we have already encountered it many times!Remember that in the first lecture we defined the ring \( \mathbb{Z}_p \) as the inverse limit \( \varprojlim_r \mathbb{Z}/p^r \mathbb{Z} \) without defining what an inverse limit is! Now that we know this, we can go back and try to understand what a p-adic number really is, as we will do in the next section.

Moreover, we can use inverse limits to give another description of the ring \( A_{\phi} \) associated to a non-Archimedean absolute value \( \phi \colon K \to \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} \). In order to do so, we need to define a new way to put a topology on any ring.

Definition 6 Let \( R \) be a ring, and \( I \subseteq R \) be an ideal. The \( I \)-adic topology on \( R \) is the coarsest topology such that \( x + I^n \) is open for all \( x \in R \) and \( n \in \mathbb{N} \).

Exercise 7 Let \( R \) be a ring, and \( I \subseteq R \) be an ideal. Show that the maps

\[ \begin{aligned}

R \times R &\to R \\

(x,y) &\mapsto x + y

\end{aligned} \qquad \text{and} \qquad \begin{aligned}

R \times R &\to R \\

(x,y) &\mapsto x y

\end{aligned}

\] are continuous with respect to the \( I \)-adic topology, i.e. \( R \) is a topological ring with respect to the \( I \)-adic topology.

We have already encountered many examples of \( I \)-adic topologies, as it is shown in the following exercise.

Exercise 8 Let \( (K,\phi) \) be a non-Archimedean, discretely valued field. Prove that the subspace topology induced on \( A_{\phi} \) coincides with the \( \mathfrak{m}_{\phi} \)-adic topology.

The properties of completeness and separateness of the \( I \)-adic topology, which we recall in the following definition, can be detected by means of an inverse limit, as we see in the next proposition.

Definition 9 Let \( X \) be a topological space. We say that:

- \( X \) is separated (or Hausdorff, or T2) if for every \( x, y \in X \) with \( x \neq y \) there exist two open subsets \( U, V \subseteq X \) with \( x \in U \), \( y \in V \) and \( U \cap V = \emptyset \);

- a sequence \( \{ x_n \} \subseteq X \) converges to \( x_{\infty} \in X \) if for every open neighborhood \( x_{\infty} \in U \subseteq X \) there exists \( n_0 \in \mathbb{N} \) such that for every \( n \geq n_0 \) we have that \( x_n \in U \).

Observe that every topological ring \( R \) is also a topological abelian group. Thus when we say that \( R \) is complete (or that a sequence is Cauchy in \( R \) ) we consider \( R \) as a topological abelian group.

Proposition 11 Let \( R \) be a ring, and let \( I \subseteq R \) be an ideal. Then \( R \) is separated with respect to the \( I \)-adic topology if and only if the map \begin{align} \varphi \colon R &\to \varprojlim_n R/I^n \\ x &\mapsto (x \, \text{mod} \, I^n)_n \end{align} is injective, and it is complete if and only if \( \varphi \) is surjective.

Proof Observe that \( \varphi \) is injective if and only if for every \( x, y \in R \) with \( x \neq y \) there exists \( n \in \mathbb{N} \) such that \( x \not\equiv y \, \text{mod} \, I^n \). This is equivalent to say that for every \( x, y \in R \) with \( x \neq y \) there exists \( n \in \mathbb{N} \) such that \( x + I^n \cap y + I^n = \emptyset \), i.e. that \( R \) is separated with respect to the \( I \)-adic topology.

Observe now that a sequence \( \{ x_n \} \subseteq R \) is Cauchy if and only if for every \( N \in \mathbb{N} \) there exists \( n_0 \in \mathbb{N} \) such that for all \( n, m \in \mathbb{N}_{\geq n_0} \) we have that \( x_n - x_m \in I^N \).

Suppose now that \( R \) is complete with respect to the \( I \)-adic topology. Let now \( \mathbf{x} = (x_n \, \text{mod} \, I^n) \in \varprojlim_n R/I^n \) and observe that the sequence \( \{ x_n \} \subseteq R \) is Cauchy, because by definition of the inverse limit we have that \( x_n - x_m \in I^m \) for all \( n \geq m \). Thus let \( x_{\infty} \in R \) be the limit of \( \{ x_n \} \) and observe that \( x_{\infty} - x_n \in I^n \) for all \( n \in \mathbb{N} \), i.e. that \( \varphi(x_{\infty}) = \mathbf{x} \) and thus \( \varphi \) is surjective.

Vice versa if \( \varphi \) is surjective and \( \{ x_n \} \subseteq R \) is a Cauchy sequence we can always find a subsequence \( \{ y_k = x_{n_k} \) such that \( y_k - y_l \in I^l \) for all \( k \geq l \). If we do so then \( \mathbf{y} := (y_k \, \text{mod} \, I^k) \in \varprojlim_k R/I^k \) and since \( \varphi \) is surjective we can find \( y_{\infty} \in R \) such that \( \varphi(y_{\infty}) = \mathbf{y} \). It is really easy to see now that \( \{ y_k \} \) converges to \( y_{\infty} \), which implies that \( \{ x_n \} \) also converges to \( y_{\infty} \) because the sequence \( \{ x_n \} \) is Cauchy. Q.E.D.

Corollary 12 Let \( (K,\phi) \) be a non-Archimedean, discrete valued field, and let \( \pi \in K \) be a uniformizer. Then \( (K,\phi) \) is complete if and only if the map

\begin{align} \left( \dagger \right) \colon A_{\phi} &\to \varprojlim_n A_{\phi}/\pi^n A_{\phi} \\ x &\mapsto (x \, \text{mod} \, \pi^n)_n \end{align} is an isomorphism.

Proof Using the previous proposition we see that \( \left( \dagger \right) \) is an isomorphism if and only if \( A_{\phi} \) is complete with respect to the \( \mathfrak{m}_{\phi} \)-adic topology. To conclude we simply need to observe that this topology coincides with the subspace topology induced by \( K \) (thanks to Exercise 8) and that \( K \) is complete if and only if \( A_{\phi} \) is complete because we can write \( K = \bigcup_{i \in I} x_i + A_{\phi} \) for some \( \{ x_i \} \subseteq K \) representing the quotient of abelian groups \( K/A_{\phi} \). Q.E.D.

Corollary 13 Let \( (K, \phi) \) be a non-Archimedean, discretely valued field, and let \( (K_{\phi}, \Phi) \) be its completion. Then we have that \[ A_{\Phi} \cong \varprojlim_n A_{\phi}/\pi^n A_{\phi} \] where \( \pi \in K \) is any uniformizer.

Examples of local fields

Let \( K \) be a local field, i.e. a topological field which is locally compact and does not have the discrete topology. We will see that on every such field the topology comes from an absolute value \( \phi \) that we can define using important concepts coming from harmonic analysis (namely, Haar's measure). We have also seen in the previous lecture that every such field is complete.Suppose now that \( K \) is non-Archimedean. Then \( \phi(K^{\times}) \) is discrete and we can describe the ring \( A_{\phi} \) as \[ A_{\phi} = \left\{ \sum_{k = 0}^{+\infty} a_k \pi^k \mid a_k \in S \right\} \] where \( S \subseteq K \) is any set of representatives for the quotient \( A_{\phi}/\mathfrak{m}_{\phi} \) which contains zero (this is Corollary 8 of the previous lecture) or as \[ A_{\phi} \cong \varprojlim_n A_{\phi}/\pi^n A_{\phi} \] using Corollary 12. In particular if \( K \) is the completion of a field \( F \subseteq L \) then we can use Corollary 13 to write \[ A_{\phi} \cong \varprojlim_n R/t^n R \], where \( R := A_{\phi} \cap F \) and \( t \in F \) is a uniformizer.

Example 14 Let \( F \) be any field, and consider the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \colon F(T) \to \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} \) defined by \( \lvert f(T) \rvert_T := c^{-\operatorname{ord}_T(f(T))} \), where \( \operatorname{ord}_T(f(T)) := \max\{ n \in \mathbb{N} \colon T^n \mid f(T) \} \) and \( c \in \mathbb{R}_{> 1} \) is any constant. Observe that \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \) is non-Archimedean and that \( \lvert T \rvert_T = c^{-1} < 1 \). Thus for every sequence \( \{ a_n \} \subseteq F \) we have that the sequence of partial sums \( \left\{ \sum_{j = 0}^n a_j T^j \right\}_n \subseteq F(T) \) is a Cauchy sequence with respect to \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \).

Consider now the field of formal Laurent series \( F((T)) \) that we defined in Example 12 of the previous lecture. Then we have an embedding \( F(T) \hookrightarrow F((T)) \) given by extending the obvious inclusion of integral domains \( F[T] \hookrightarrow F[[ T ]] \) to their fields of fractions. Moreover the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \) extends to \( F(( T )) \) by setting \[ \left\lvert \sum_{n = n_0}^{+\infty} a_n T^n \right\rvert := c^{-n_0} \qquad \text{where} \qquad a_{n_0} \neq 0 \] and it is not difficult to see that \( F(( T )) \) is complete with respect to this absolute value. Indeed a sequence \( \left\{ \sum_{k = k_0^n} a_k^n T^k \right\}_n \subseteq F(( T )) \) is Cauchy if and only if the sequence \( \{ k_0^n \}_n \) has a minimum \( k_0^{\infty} \) and for every \( k \in \mathbb{Z}_{\geq k_0^{\infty}} \) there exists \( n_k \in \mathbb{N} \) such that for every \( l \in \mathbb{N}_{\leq k_0} \) and for every \( n, m \in \mathbb{N}_{\geq n_k} \) we have that \( a_l^n = a_l^m \). Thus we can define a new sequence \( a_k^{\infty} := a_k^{n_k} \) and it is easy to see that \( \sum_{k = k_{0}^{\infty}}^{+\infty} a_k^{\infty} T^k \) is the limit of the Cauchy sequence that we started from.

Finally if \( F(T) \to L \) is a morphism of valued fields we can use the fact that any sequence of partial sums \( \left\{ \sum_{j = 0}^n a_j T^j \right\}_n \) is Cauchy (if \( \{ a_j \}_j \subseteq F \)) to see immediately that this morphism extends (uniquely) to a map \( F(( T )) \to L \). Thus we have proved that \( F(( T )) \) is the completion of \( F(T) \) with respect to the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \).

To do so in an effortless way we could observe that \( T \in F(T) \) is a uniformizer for the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_T \) and thus if \( (K,\Phi) \) is any completion of \( (F(T), \lvert \cdot \rvert_T) \) we have that \[ A_{\Phi} = \left\{ \sum_{k = 0}^{+\infty} a_k T^k \mid a_k \in F \right\} \cong F[[ T ]] \] which implies that \( K \cong F(( T )) \).

We can do something similar for the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_p \) on the field \( \mathbb{Q} \).

Definition 15 The field of p-adic numbers \( \mathbb{Q}_p \) is the completion of the field \( \mathbb{Q} \) with respect to the absolute value \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_p \). We denote its unit ball by \( \mathbb{Z}_p \) and we call it the ring of p-adic integers.

We can give two alternative descriptions of \( \mathbb{Q}_p \) as follows:

- using Corollary 8 of the previous lecture we can observe that \[ \mathbb{Q}_p = \left\{ \sum_{k = k_0}^{+\infty} a_k p^k \mid a_k \in \{ 0,1,\dots,p - 1 \}, \ k_0 \in \mathbb{Z} \right\} \] because \( p \in \mathbb{Q} \) is a uniformizer for \( \lvert \cdot \rvert_p \) and \( A_{\lvert \cdot \rvert_p}/\mathfrak{m}_{\lvert \cdot \rvert_p} = \mathbb{Z}_{(p)}/p\mathbb{Z}_{(p)} \cong \mathbb{Z}/p\mathbb{Z} \);

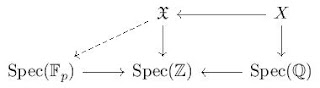

- using Corollary 13 we get that \[ \mathbb{Z}_p \cong \varprojlim_r \mathbb{Z}_{(p)}/p^r \mathbb{Z}_{(p)} \cong \varprojlim_r \mathbb{Z}/p^r \mathbb{Z} \qquad \text{and thus} \qquad \mathbb{Q}_p \cong \operatorname{Frac}\left( \varprojlim_r \mathbb{Z}/p^r \mathbb{Z} \right) \] which is how we defined \( \mathbb{Z}_p \) in the first lecture.

Conclusions and references

In this lecture we managed to:- define inverse limits and the \( I \)-adic topology on a ring \( R \);

- prove a relation between the completeness of the \( I \)-adic topology and inverse limits;

- study in detail the examples of \( F(( T )) \) and \( \mathbb{Q}_p \).

- Section 2 of these notes by Stevenhagen;

- Chapter 8 of these notes by Pancratz (based on a course by T. Dokchitser).

Comments

Post a Comment